Recalcitrant scripts!

I promised to write about the script and why it's such a particular challenge, so here we go!

Just to explain, The Big Meal is unique in its structure in that there are eight actors onstage performing multiple generations in a family in 90 minutes. It's been done before; in fact, Dan LeFranc, the playwright, was inspired by Thornton Wilder's The Long Christmas Dinner (which is also often compared to the later The Dining Room by A.R. Gurney), so any resemblances you may see to those plays are well noticed! (If you're craving further dramaturgical/literary discussion, I refer you to this wonderful essay from artistic director Tim Sanford regarding the Playwrights Horizons production.) However, even though the convention isn't brand new, I've never felt the play is by any means derivative; in fact, I think having an understanding of the ground those plays have previously covered really highlights the impact of this particular day and age in which The Big Meal was written. Which is just a complicated way of saying it is a modern play that is very much of OUR time, and that's important because it allows us, as the audience, to recognize ourselves and our family members in the writing. That's the key to enjoying this play: you've gotta see yourself and your family. And Dan accomplishes that by creating the mundane, everyday conversations that this particular family has.

Okay, so on to the script: it turns out that writing normal everyday speech is really hard to do because we tend to talk over each other all the time. We overlap, we cut each other off, and we just plain don't listen to each other. It's frighteningly easy to do in regular life, but writing that mess down, and even worse, figuring out how to then say it, is sort of crazy. So Dan had to figure out a way to present the script in the effort to help make sense of it all.

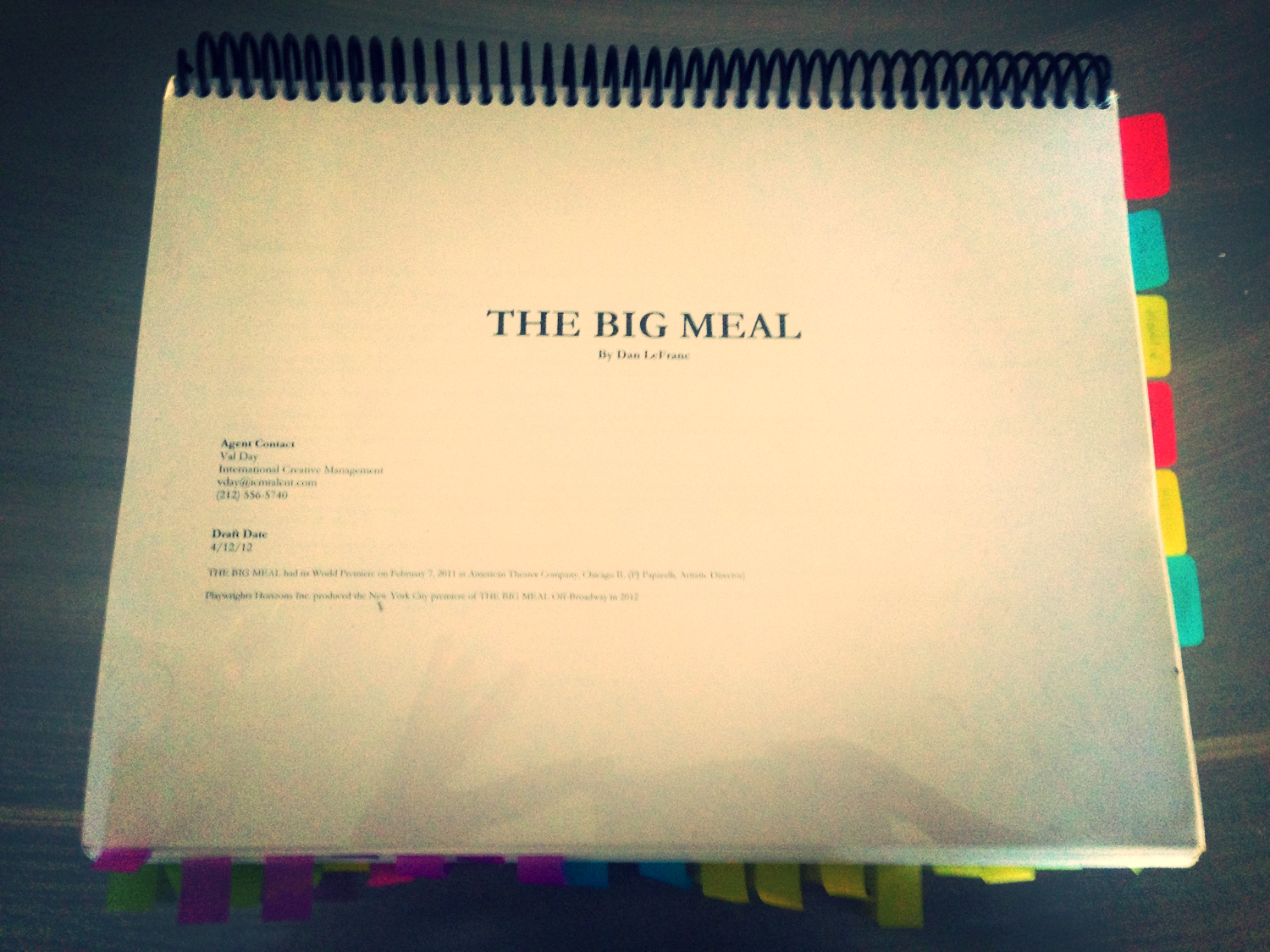

Big meal = big script.

Technicolor Life by Jami Brandli

First, just as a reminder, here's what a normal script looks like. (This is from Technicolor Life by Jami Brandli, which I'll be writing about soon!)

See the cutoff up there? With just a couple of dashes, the playwright tells the actor to jump in on the line.

But what happens when two actors are supposed to be talking simultaneously? Well, sometimes playwrights will have two conversations running down the page side by side until the overlap ends. No big deal.

But what happens when three, four, five, six, or seven people are supposed to be talking at the same time? Well, that's when you get something that looks like this:

Guys, this is one of the less complicated pages.

This is the first time I've ever had to pull out a ruler to figure out when I'm supposed to say my line. Also the first time I've needed to draw arrows in my script to keep track of my speaking partner(s). All of which is to say: It's an intimidating thing to read when you first look at it.

To top it off, we were dealing with a couple of different versions, depending on what people were most comfortable carting around in rehearsal. You can see from the top picture that my script is ENORMOUS. It weighs a million pounds. Some folks were not into that, so they used the published version, which cut down on the weight. However, the different versions occasionally had different alignments, so it was challenging to figure out just when we were supposed to talk, and precision is key in this play. Sometimes we had to agree on what made the most sense.

Also challenging: memorization. Since this wasn't a new play, my plan was to come in with all my lines memorized! I was gonna be so prepared and amazing! . . . until I realized that I was just running down the page looking solely at my Woman #3 column. Which meant I could only say my lines in quick succession, like a terrible makes-no-sense poem. Eventually, I gave up on the one-woman-show version and waited for rehearsals to start. This was definitely an aural learning through repetition situation.

There's only one person NOT talking at this moment, I think.

The last challenge, and I have to give a shout out to our director Kirsten Brandt here for being so amazing and patient, was that when eight people are all talking at the same time, the temptation is to shout to be heard. I mean, as an actor, I want to be heard, right? My line is important! Listen to me! So we were all shouting at each other sometimes, which was very loud, but somehow also resulted in no one being able to hear each other. Obviously, the solution was to identify the more important conversations and less important conversations, and it was up to Kirsten to be the conductor and tell us who needed to lay off on the volume.

All this just to get the same effect of how we speak to each other every day!

Someone asked at a talkback if this has made us members of the cast worse about interrupting each other. I jokingly said, "No, I started out interrupting people, so it's the same for me!" But really, I think that this has made me much more aware, especially in big groups, that everyone is having their say, whether or not he or she voices it loudly. I'm taking the time to listen more carefully. That is, when I'm not shouting to be heard. :)